© 2007 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://www.damninteresting.com/the-flying-saucers-of-north-america/

Under the cover of darkness on 07 October 1959, a convoy of military vehicles escorted a flatbed truck through the abandoned streets of Malton, Canada just outside of Toronto. Local police had arranged to clear the route from a top-secret aircraft hangar to Toronto harbor, so the drivers paid little mind to traffic laws as they traversed the city. Upon arrival at the harbor the concealed cargo would be transferred to a US Navy tugboat, where it would make its way to a special NASA research facility in the United States under close guard. The exaggerated security was understandable given the circumstances: The secret stowed beneath the truck’s tarps was a real-life flying saucer.

If eyewitness reports are to be believed, the skies over the United States were swarming with unidentified flying objects during the early 1950s. Such sightings were not unheard of previously, but never before had the reports been so frequent and widespread. Some people suspected hoaxes and hysteria, and others speculated about otherworldly origins. While few doubted that there was something strange lingering in America’s air, US military leaders were skeptical that the blobs of light were piloted by moon-men or martians. They were quite concerned, however, about the possibility that the blob-occupants were Russian-speaking.

There had long been credible rumors of secret Nazi “flying disk” attack planes being tested during the final few months of the Third Reich, and with the sharp rise in saucer sightings US officials wondered if Soviet scientists might have plundered and perfected the technology. Fortunately, the US wasn’t too far behind; by the mid 1950s they had their own flying saucer program well underway.

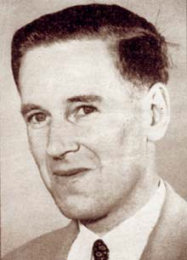

The United States’ venture in flying saucer technology began in 1953 during a routine visit to Avro Aircraft, an outfit located in Malton. A gaggle of US defense experts were inspecting the shiny new CF-100 fighter jet when their tour was commandeered by a company engineer named John C. M. Frost— better known as “Jack” Frost. Frost was a highly accomplished aeronautics designer, as well as the head of the company’s Special Projects Group. He showered the unsuspecting Americans with enthusiasm and information regarding one of Avro’s secret but recently abandoned ideas. Frost’s “Project Y” was a flat, wedge-shaped theoretical aircraft intended to lift off vertically like a helicopter while also possessing the speed, agility, and high-altitude capabilities of a jet fighter.

The Americans were understandably intrigued, particularly when Frost shared a series of sketches outlining further advancements. His tantalizing new idea described an extremely maneuverable frisbee-shaped aircraft, capable of vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) and able to reach an altitude of 100,000 feet and speeds up to Mach 3.5. The US military eagerly adopted the orphan project, rejuvenating the research with $750,000 in funding and renaming the platform to “Weapons System 606A.”

US interest in VTOL aircraft was motivated largely by the lingering threat of nuclear war. Just a few years earlier, Soviet scientists had exploded their first atomic bomb using uranium liberated from the Nazis and plans pilfered from the Americans, an event which prompted some significant changes in defense philosophy. Military strategists were concerned about the fact that conventional jets had to be concentrated around airfields in order to remain practical, making each military airbase a likely target and a liability in the event of a nuclear war. In contrast, a widely dispersed Air Force made up of supersonic VTOL flying saucers would be much more resilient. The military men were tickled at the prospect.

Over the following months the members of the Avro Special Projects Group labored under a veil of secrecy in their secure hangar. Only a handful of employees had access to the building, and armed guards at each door scrutinized all credentials. In the company machine shop, workers fabricated individual parts based on separate schematics, and upon completion all drawings were taken away in special bags to be destroyed. Few had even the vaguest notion what sort of clandestine goings-on were being undertaken in the notorious Experimental Hangar.

A rudimentary version of Frost’s flying saucer slowly materialized over the following months. It employed a unique configuration of his own design, sporting a large central turbine that was driven by the thrust of six inward-facing Viper jet engines. The rapidly spinning turbine would act as a gyroscope to keep the machine balanced, while also sucking air from above the craft and squirting it out through a series of downward-pointing vents around the lip of the saucer. At low altitudes, this would provide a ground effect cushion of air to support the vehicle’s weight, and the thrust could then be routed through a network of ducts and flaps to rapidly launch the craft into the sky in any direction. Frost and his team affectionately referred to this unique design as the “pancake engine.”

When the aviation experts of the Special Projects Group first began unmanned testing inside a special rig, the prototype proved problematic. The contraption had a tendency to ooze oil, and on several occasions it caught fire as a result. One nearly-fatal incident with a rogue jet engine left workers very wary of the apparatus, and Frost concluded that the best course of action would be to scale the design down into a more manageable prototype.

In 1958 Frost approached his military investors with a revised concept. This new layout was more compact at only eighteen feet in diameter; and it was less complex, with three jet engines rather than six. His crew called their new concept the Avrocar. Air Force officials were delighted that they might see a working prototype sooner than expected, and the US Army expressed interest in using the new pint-sized version as a “flying jeep.” Members of Avro’s management were similarly excited, envisioning a whole line of Avrocar spinoffs, such as the Avrowagon for the jet-setting family of the future, and the Avroangel for use as an airborne ambulance. Many of the military personnel who were privy to the project suspected that the Avrocar and its cousins would one day render the helicopter obsolete.

In May of 1959, the first Avrocar prototype was carted out of its top-secret hangar for its initial tethered flight test. The prototype requirements had originally called for a ten-minute hover capability and twenty-five mile range, but Frost calculated that his team’s prototype would be capable of reaching 250 miles per hour, 10,000 feet in altitude, and 130 miles in range. But as the unmanned vehicle struggled to hover inside its protective rig, the team of engineers were discouraged to see that its performance was much poorer than anticipated. It was soon discovered that the vehicle was inhaling its own hot jet exhaust, causing a sharp reduction in engine efficiency. A few months’ tinkering did little to circumvent the problem, so the Special Projects Group decided to pack it on a flatbed truck and send it to the US tugboat for wind-tunnel testing at NASA. In the meantime, they revised the internals of the second model.

On 29 September 1959, the reworked Avrocar #2 was ready for testing. Test pilot W.D. “Spud” Potocki clambered into the tethered experimental vehicle and strapped himself into the cramped cockpit. The trio of engines roared to life, and Potocki verified that the instrument panel didn’t indicate any problems. He gently increased the throttle, and the violently vibrating vehicle responded by ponderously pulling its feet from the earth. He inched the craft into the air as he got a feel for the controls, but at about 3-4 feet up something unexpected happened. The craft tilted sharply to the side, and began to oscillate uncontrollably like a dropped hub cap spinning on its rim. The test pilot immediately cut the engines, and the Avrocar dropped to the ground.

Through the rest of 1959 and the two years that followed, Frost and his team tested a series of modifications which made gradual improvements to the aircraft’s abilities. To resolve the “hubcapping” problem, a central stabilizing jet was added by drilling holes in the bottom center of the body, and the team enhanced the vehicle’s lift characteristics by installing a reworked flap system. By April 1961, the design was sufficiently improved that “Spud” Potocki was able to hover around the compound with relative ease, at times reportedly reaching speeds over 100 miles per hour. On cold days, the Avrocar’s wind could suck the frozen water off the tops of the puddles and the glassy sheets of ice would float through the air. But for all of its improvements, the Avrocar was still dangerously unstable while maneuvering, and unable to safely hover much higher than 3-4 feet above the ground. The cockpit was also plagued by an oppressive amount of heat and noise from the three internal jet engines.

As ever, Frost’s mind was bristling with potential solutions, but in spite of the incremental improvements the US military had become disenchanted with the flying saucer concept. After spending eight years and $7.5 million, the Air Force officially canceled funding in late 1961, and the Avrocar project collapsed under its own weight. Jack Frost left Canada an embittered man, but he eventually settled down at Air New Zealand where he applied his ingenuity to more ordinary aircraft improvements such as hydraulic tail docks and air-conditioning systems. He found some measure of joy in his new work, but he never really stopped grieving for his unrealized flying saucer ambitions. Many of his discoveries went on to benefit the development of the modern hovercraft, a vehicle which some fittingly described as nothing more than an Avrocar in a short rubber skirt.

Although Jack Frost died in 1979, he was posthumously inducted into Canada’s Aviation Hall of Fame in 2001 for his novel ideas in the art of aeronautics. Both of Frost’s Avrocar prototypes are still somewhat intact today; one is on display at the US Army Transportation Museum at Fort Eustis, Virginia, and the other is collecting dust and rust in a National Air and Space Museum storage building in Silver Hills, Maryland.

Perhaps with a bit more time and few more resources, Jack Frost’s ingenuity and tenacity could have eventually brought this revolutionary aircraft to fruition. Had it not been for the shortage of patience and imagination on the part of military officials in the 1960s, we might all be hovering around in our Avrowagons today, bemoaning the price of jet fuel and dodging supersonic soccer moms who are too busy talking on their video cell phones to keep their eyes on the sky. Once again, the future that might have been seems far more impressive than the reality that we must accept.

© 2007 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://www.damninteresting.com/the-flying-saucers-of-north-america/

Since you enjoyed our work enough to print it out, and read it clear to the end, would you consider donating a few dollars at https://www.damninteresting.com/donate ?

Let me be the first to say that the prospect of drunk fliers crashing into my roof is enough to be thankful that we can not have one of these craft as easily as we can go out and buy a car.

Wow, very good read.

DI indeed

I saw this on Discovery. The video footage didn’t instill hope: flew like a janky firsby thrown with your left hand.

I can’t imagine anything aerodynamic in that shape.

Also I will second TimWhit’s comment; if we are to have flying cars, they shall have to be automated.

This was really a side-project for Avro. Their real claim to fame was the Avro Arrow. It should have been…well…it WAS the best jet fighter in the world at the time, by far!

The US military was blown away by it and it in turn blew away their “lofty” requirements.

The Avro Arrow made it an easy assumption, that if it weren’t for moronic politicians cancelling the program and scrapping all the finished aircraft, that Canada would have easily been the leader in jet fighter manufacturing for quite some time. At least a lot of the engineers and design team went on to produce other aircraft for other companies, thus making the Arrow somewhat beneficial.

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/6/6b/AvroArrow1.jpg/300px-AvroArrow1.jpg

http://www.exn.ca/news/images/a/arrow-203ongroundbig.jpg

Mach 2.5 Combat speed

Mach 1.0 Cruising speed

Ceiling of nearly 70,000

It was an impressive bird considering this was in the 1950’s, too bad foolish politicians had to get in the way and bugger it all up!

http://www.moller.com/xm2.htm

Check out the image of the xm2.

I am wicked pumped with this reality… i think flying saucers are better off in story land. You can’t burn rubber in a saucer… what would you say… “yea I really laid some.. air… you.. punk”

No appeal. But its nice to know what could have been.

I was really disappointed that the article is mostly about Canadian and U.S. attempts to design a flying

saucer. Though interesting I would much rather have read about the flying saucer that was hauled off by a

USN tug in the first paragraph. It seems like the first paragraph is a teaser that goes nowhere. :(

Now I profess absolutly no knowledge about aircraft but I thought the auto liftoff problem had been solved by now, with the AV-8B Harrier(?). I remember seeing a demo of one of these at a fair, and was awed at the planes ability to rise strait up from the ground and hover in place like a helecopter. (Ha!Leave it to the British to invent a plane that can curtsey!.) Any how, what would prevent the same propulsion in a smaller craft? Oh , and why is the round or saucer shape so nessesary?

USNSPARKS, the first paragraph is describing the delivery of the original Avrocar prototype to NASA for wind tunnel testing. See paragraph 11.

Tink, there are a number of VTOL-capable jet aircraft currently in existence, including the Hawker Harrier and the Yakovlev Yak-38 Forger & Yak-141 Freestyle. These are more conventionally designed aircraft with multiple engine exhausts spaced around the bottom of the plane to allow it to direct engine exhaust downwards and support itself in a hover. They’re quite different from the flying saucer designs discussed here, which were designed around a fixed downward-pointing turbine engine which was supposed to stabilize the craft. I think that has a lot to do with the radial symmetry of the design, since a traditional design would distribute the weight unevenly around the engine, and affect the balance of the plane.

Ahh, I see, thank you, Dixie Flatline!

geez thats freaky its either military stuff or aliens and i dont like either! 1 changes combat forever the other changes earth.

Tink said: “Ahh, I see, thank you, Dixie Flatline!”

Additionally, the AV-8B was plagued with accidents. I was a helicopter mechanic in the late 70’s/early 80’s in the Marine Corps. I believe we had the largest contingent of these beasts, and it seemed like every week we heard about another one of them crashing…I believe they are a LOT better about it now, but that may be because they don’t use them much anymore.

None-the-less, it was pretty cool to watch one of them take off from the deck of a ship, hover for a moment, rather like a large clunky mosquito, and then kind of drop the tail and shoot off into the wild blue yonder. Still, I wouldn’t have traded my main rotors in for one! ;o)

The whole Nazi saucer thing is largely a fiction kept alive by neo-Nazis. Though Germany did amazing work during WWII (rocketry, for example), I very much doubt they had the resources to construct, or even develop a working saucer. Also, has anyone noticed that this story inadvertently discredits Roswell and other crashed saucer stories?

Nitpicky Dept.: In the second-last paragraph, wouldn’t the one sentence be less bumpy if it read “rust and dust”?

Dave Group said: “The whole Nazi saucer thing is largely a fiction kept alive by neo-Nazis. Though Germany did amazing work during WWII (rocketry, for example), I very much doubt they had the resources to construct, or even develop a working saucer.

Exactly! :) all the fictional weapons that the nazis supposedly where ‘just-about-to-reveal-moments-before-they-lost’, and literally seem to have come straight out of old sci-fi flicks, are quite entertaining but [i]absolutely[/i] bogus. I understand the importance of good story telling but the truth is good enough for me.

they never developed working nukes, they never had flying saucers, they never cured the common cold, and they didnt land on the moon. Basically nazis made lots of guns, killed a lot of people, made their guns bigger, then lost. Let’s leave it at that.

inmyopinion said: “Exactly! :) all the fictional weapons that the nazis supposedly where ‘just-about-to-reveal-moments-before-they-lost’, and literally seem to have come straight out of old sci-fi flicks, are quite entertaining but [i]absolutely[/i] bogus. I understand the importance of good story telling but the truth is good enough for me.

they never developed working nukes, they never had flying saucers, they never cured the common cold, and they didnt land on the moon. Basically nazis made lots of guns, killed a lot of people, made their guns bigger, then lost. Let’s leave it at that.”

Do we have a hard time crediting the enemy? Sheesh! Yeah the Nazis were terrible…yeah they were evil…but they did some darn interesting and intelligent things!

They were within spitting distance of developing nuclear weapons, they had a great rocket program and they very well could have developed a remarkable flying disc.

Me? I have no problems crediting the Nazis as a formidable foe and having brilliant minds. Remember, they only “lost” because their leader had a bit of a breakdown. You might be speaking German today if he wasn’t so insane with power.

Dave seemed to have a decent grasp on things…too bad you took it, ran with it, dumb-ified it and then posted it. Let’s try not to pretend that you are totally aware of all the goings on in Nazi Germany during war time. They could have created a time machine seconds before bombs blew it up for all you know. Those “fictional weapons” that you speak of may have just been the tip of the iceberg.

Hmm… On the one hand it’s, in hindsight, baffling how long it took to realize this idea was not going to work. On the other hand there is this huge… yearning for a practical three dimensional vehicle. The Moeller sky car is a great example. I’ve been following it’s development for years. I’m amazed that they keep going, keep getting funding, keep promising it’s just around the corner. But the product never comes. Great scam.

HarleyHetz said: “Additionally, the AV-8B was plagued with accidents. I was a helicopter mechanic in the late 70’s/early 80’s in the Marine Corps. I believe we had the largest contingent of these beasts, and it seemed like every week we heard about another one of them crashing…I believe they are a LOT better about it now, but that may be because they don’t use them much anymore.

None-the-less, it was pretty cool to watch one of them take off from the deck of a ship, hover for a moment, rather like a large clunky mosquito, and then kind of drop the tail and shoot off into the wild blue yonder. Still, I wouldn’t have traded my main rotors in for one! ;o)”

Ah Ha! I wondered why we hadn’t heard more about these being used. Very interesting, Thank you too, dear!

They were within spitting distance of developing nuclear weapons

No they really where not even close. And the tales of a nuclear reactor are also exagerated, they worked on one nuclear reactor but used a flawed design and it never would even work. Further, they didnt even had the purified deuterium for it, those barrels that everyone makes such a big deal over contained ordinary water with a slightly elevated level of deuterium. They where probably going to try to purify it further but there is no indication they never generated any significant amounts of deuterium.

they had a great rocket program and they very well could have developed a remarkable flying disc.

The had rockets which where ahead of what the allied had, but like all pioneering technology the rockets where highly ineffective and mostly for show. They wheren’t accurate enough to replace bombs or to be adapted for ground-to-air. So it would never have won the war for them. What it did do however, was scare the allied, which probably only worked against Nazis in the end. The Nazis kept spreading propaganda aimed to give the Allied the feeling that the Nazis where about to discover something that would actually win the war, but that made the Allied more alert while it was intented to make them surrender.

Ironically, some of that propaganda survived and is being treated as history by conspiracy theorists.

Me? I have no problems crediting the Nazis as a formidable foe and having brilliant minds. Remember, they only “lost” because their leader had a bit of a breakdown.

No they lost because they tried to take over the world. That simply isn’t possible, not for any force or empire. There are too many forces who’s interests conflict with someone else being in charge. Even among the ranks of the nazis, there where powerplays. People that are out to get power, NEVER share power.

As for brilliant minds, they simply did what other people didnt want to do. Nazis didnt have genes allowing them to think of superweapons that other people couldn’t, there where brilliant scientists neatly distributed over the industrialized world who thought up all manner of amazing stuff. But the nazis where actually planning to take over the world, and where interested in developing tools to do exactly that. Nazi Germany was simply specialized in war.

Other countries where still running normal everyday affairs while Germany was already preparing, on evey level, for war. Other countries had many different groups of people with their own goals, in Germany those groups where either being silenced or united by hate.

Such unifications being conflicting groups never last long, just look at Russia and America. The same counts for all the opposing groups in Germany, like the officers that tried to assassinate Hitler.

Also, whether you try to rally troops or even an entire nation, the effects of warspeeches and propaganda only lasts for a little while before people get tired and want to go on with their lives. Nearing the end, the Germans where already getting tired of a war which seemed to go on for ever and didnt go at all as they had anticipated, while the Allied where still pushing themselves because they knew they otherwize would not have a home to go back to.

You might be speaking German today if he wasn’t so insane with power.

If he hadn’t been insance with power, what would the motivation have been to try to take over the world?

Dave seemed to have a decent grasp on things…too bad you took it, ran with it, dumb-ified it and then posted it. Let’s try not to pretend that you are totally aware of all the goings on in Nazi Germany during war time.

You seem to think you are? I have read the same websites you seem to have read. And they are like all conspiracy websites, full of crap. The add facts which seem to be made up on the spot, and details change per website, but in the end it is painfully obvious that many of the tales of Nazi superweapons are really the same story which was copy-pasted over numerous different websites after the first guy ripped it from a 3th rate book.

They could have created a time machine seconds before bombs blew it up for all you know. Those “fictional weapons” that you speak of may have just been the tip of the iceberg.”

I hope youre joking.

You might be speaking German today if he wasn’t so insane with power.

Or if you took German classes.

Another note on the AV-8B — I seem to recall that in Desert Storm, they turned out to be more vulnerable than predicted to IR-homing missiles. On a conventional jet fighter, a heatseeker will home in on the engine exhaust at the tail of the plane, and when the warhead explodes, it may damage or destroy the engine, but the pilot and the rest of the plane will be less damaged, giving the pilot a chance to bring the bird home or at least punch out in good order. On the Harrier, the engine exhausts are at the four corners of the fuselage, so a heatseeker tends to average them out and hit dead-center in the plane’s underbelly, destroying it before the pilot has a chance to do anything.

With respect to the Nazis — yes, they did have some very advanced aeronautical research, and some impressive designs that never made it into production, or were never produced in significant numbers. The best example of a weapon that was crippled by Hitler’s obsessions was the Me 262 jet fighter, which was a highly effective interceptor that could have done a lot more damage to Allied bombing raids if Hitler hadn’t insisted that it be equipped and used as a bomber itself.

The German nuclear-weapons program was more or less a lost causefrom the start, although from the other side of the Atlantic, it certainly appeared a credible threat. The Germans decided early to pursue reactors moderated by heavy water rather than graphite, based on some inaccurate measurements of graphite’s effectiveness as a moderator, and they never had the heavy water or supplies necessary to get beyond basic experiments. After the Vemork heavy-water extraction plant in Norway was crippled by Allied commando operations and then destroyed by bombing raids, they really had no source for heavy water. (Not to mention that most of their best physicists had fled to the US and were working on the Manhattan Project, while Heisenberg and the other German scientists may not have been that enthusiastic about building Hitler a nuclear bomb in the first place.)

Ultimately, even if they had managed to bring some of their advanced weapons projects into production, the Nazis were doomed by the fact that they were being vastly out-produced by the US industrial machine, which was supplying the war against them on two different fronts — the Allied forces in the West and the Soviets in the East — as well as the war against the Japanese in the Pacific. As long as the Germans were facing an enemy who could manufacture more Sherman tanks than the German factories could produce 88mm anti-tank shells to kill them with, their situation was fundamentally hopeless.

(Now, one can imagine a few situations where a few more advanced weapons came online to slow the Allies down than they did in real life, and also, preferably, where Hitler was assassinated and replaced by someone with a bit more common sense. In a scenario like that, I could see some sort of negotiated peace happening that left Nazi Germany intact as a sovereign nation. That’s if the Germans were being led by someone willing to make a deal, and if the Allies were taking serious enough losses to make them think twice about pushing for unconditional surrender if there was an alternative on the table. That is, however, still quite a stretch.)

“gaggle of US defense experts” – made me laugh out loud. Thanks. Very interesting

130 mile range? Seems a bit short. Could that be a typo?

I think with the advances in computerized flight controls, getting something like this off the ground might be more likely today, but Moller will never do it. He’s little more than a con man.

Part of me hopes the flying saucer concept does become reality, just so long as it isn’t made as ubiquitous as the automobile; with all the people who have difficulty navigating two dimensions, I’d hate to see how screwed up traffic in 3D would be.

Jeffrey93 said: “This was really a side-project for Avro. Their real claim to fame was the Avro Arrow. It should have been…well…it WAS the best jet fighter in the world at the time, by far!

The US military was blown away by it and it in turn blew away their “lofty” requirements.

The Avro Arrow made it an easy assumption, that if it weren’t for moronic politicians cancelling the program and scrapping all the finished aircraft, that Canada would have easily been the leader in jet fighter manufacturing for quite some time. At least a lot of the engineers and design team went on to produce other aircraft for other companies, thus making the Arrow somewhat beneficial.

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/6/6b/AvroArrow1.jpg/300px-AvroArrow1.jpg

http://www.exn.ca/news/images/a/arrow-203ongroundbig.jpg

Mach 2.5 Combat speed

Mach 1.0 Cruising speed

Ceiling of nearly 70,000

It was an impressive bird considering this was in the 1950’s, too bad foolish politicians had to get in the way and bugger it all up!”

sorry, but speed does not make a good fighter

it does make a good interceptor

the F-16 and F-18 are great because they can out turn anything.

that and pilot awareness are what make great fighters.

What was the other airborne vehicle that prompted these same comments a while ago? This seems familiar…

Oh, about my comment above, I was referring to the comments about how dangerous it would be if every civilian was driving a flying machine instead of a car.

“Comment #3 (March 17th, 2007 at 2:00 pm)

brienhopkins says:

I saw this on Discovery. The video footage didn’t instill hope: flew like a janky firsby thrown with your left hand.”

my left hand happens to through a frisbee better than most right handed people thank you very much

My grandfather worked as a tool & die maker in that “secret shop” in Malton. He worked on the Avrocar amongst other projects, and it is true all of the tools and blueprints were removed “overnight” when the project stopped at this location.

Remember, they only “lost” because their leader had a bit of a breakdown.

You’re an idiot. He had a “breakdown” (aka killing yourself because you’re a dumbass and it’s over) AFTER they had already lost.

wargammer said: the F-16 and F-18 are great because they can out turn anything.

no, the F-22 FAR out turns them both

main design flaw with this thing (other than being unstable)…no room to store fuel for 3 engines = no distance = no use

The explanation I’ve been given for the saucer shape is that the craft could direct the airflow over it and the Bernoulli effect would generate additional lift. Unlike an airfoil, it could do this in different directions. Basically an extension to the flying wing concept in this regard.

Also, a saucer can be aerodynamic – consider that it’s a flying disk that holds the world’s record for the farthest human-thrown object.

…well, if the aeronautical types can figure out a way to make a wing fly without a fuselage, given enough time (and money), I’m sure someone will figure out a way to make a metal saucer fly thru the air with the greatest of ease…with some degree of stability.

I know everyone will kill me for this but… FIRST!

I think the hovercraft was a cool idea. A shame that It was tanked. (Haha, get it?)

Anyway, at least I can say UFOs exist in another way!

portsmouth101 said: ” …

I think the hovercraft was a cool idea. A shame that It was tanked. (Haha, get it?)

… “

I’m afraid I don’t get it???

portsmouth101

I dont get it either, please explain your whole comment

another viewpoint said: “…well, if the aeronautical types can figure out a way to make a wing fly without a fuselage, given enough time (and money), I’m sure someone will figure out a way to make a metal saucer fly thru the air with the greatest of ease…with some degree of stability.”

Actually, in modern aeronautics, instability can be a plus. Modern jetfighters are only able to make the neckbreaking manouvres they are capable of making because the designs are made purposefully unstable. Ofcourse, this means that high tech measures such as computerchips are required to keep the plane stable during any routine manouvre. The instability is only allowed to express itself when turns are made.

I like to think of it as enslaved chaos. Then again, im crazy.

So if saucers are inherently unstable, this might actually be considered an attractive characteristic of that shape. However, such instability would be based solely on atmospheric drag… what good THAT does in outer space, only God and the aliens know.

…there is no “atmospheric drag” in space…unless you want to consider running into a meteor, meteorite, asteroid or hemorrhoid…a drag!

another viewpoint said: “…there is no “atmospheric drag” in space…unless you want to consider running into a meteor, meteorite, asteroid or hemorrhoid…a drag!”

ehm yeah, that was my point

They are real, I have proof

‘n Can’t believe everybody’s making such a storm in a teacup over a saucer.

This site used to be cool, but it’s quickly approaching lameness. There are never any new articles, and I’m tired of seeing the reruns. I know how to use the archives–if I want to read old articles I can look them up myself. I used to get on here every day, but after seeing the same headline day after day, I stopped. sigh…

Is it just me, or is this the perfect time to argue about evolution for a few hours?

My hovercraft is full of eels!

@JM: you are the perfect illustration of the exaggerated sense of entitlement many people seem to have these days. do you really think Allan and his gang OWE you something? they write articles to amuse you, for free, without ads, and you’re bitching about it? jesus. if you don’t like the site, then go read elsewhere.

@Allan B.: maybe the psychology of bitchy over-entitlement would make a good future article. :)

oops… sorry Alan, i just noticed i spelled your name wrong.

Tink said: “Ah Ha! I wondered why we hadn’t heard more about these being used. Very interesting, Thank you too, dear!”

Damn Interesting article but I felt I had to defend the British built Harrier after all its not often we Brits manage to lead the world on something!! (other than Concorde (nod to the French as well) and Lynx the only helicoptor capable of flying upside down!). The Harrier is still unique in the fact that it is the only jet aeroplane in the world capable of reverse flight (admittedly not much use in combat) and true vertical takeoff. The other aircraft mentioned are only capable of short takeoff and landing.

Secondly, Harrier has been involved in and proved itself in many combat theatres around the world most notably during the Falkland isles conflict. During this conflict the Harrier was outnumbered and pitted against the technically superior supersonic Mirage III fighter. The British aircraft had considerable success over the islands with 22 confirmed kills with no losses. The more important thing to come out of this combat was the versatility of the aircraft, it was perfectly at home as a fighter and ground support bomber.

Currently the Harrier operates for the RAF in a similar way to the A10 Tankbuster (without the friendly fire incidents!) and has been involved in both Afghanistan and Iraq.

I’m not saying it is the perfect aircraft, however, it does have some severe lilitations. Due to the way it uses its vectored thrust its range is limited when fully laden. That fact also means it is not practical for it to use vertical takeoff when fully loaded as it would use to much fuel, they operate a Short Take Off Vertical Landing (STOVL) strategy instead. Also due to the fact that it was designed in the late 60s it lacks the fly by wire computer technology of the modern fighter. The Harrier has an incredibly and pilot intensive control system, it is no coincidence, therefore, that most of the Harriers in the field have been lost to pilot error and equipment failures.

I can’t say I won’t shed a tear when the Harrier is finally decommisioned completely as it is a tremendous testament to the inginueity and foresight of its designers. But unfortunately whilst the idea of the vertical take off aircraft is still state of the art the technology used to solve the problem most definately needs updating.

On a last note I wonder whether the Joint Strike Fighter will be able to take a bow after delivering its payload?

(BTW. I usually make a point of not getting attached to military aircraft but I was overawed as a child when I saw two of these beasts nod to to the crowd at Cosford air show)

JM said: “This site used to be cool, but it’s quickly approaching lameness. There are never any new articles, and I’m tired of seeing the reruns.

Lately there have been several reruns, yes, but not the 100% that would be required for there to be “never any new articles”. Hyperbole doesn’t help. Did you see Alan’s comment at the head of the “‘Wow!’ signal” article?

Alan Bellows said: “This should be our last classic article before we return to our normal posting schedule… thanks for your patience!”

Mr. Bellows & Co. have been preoccupied with the preparations for a book of DI articles, as you would know if you’ve been reading carefully. They’ve been really busy and haven’t had as much time as they’d like for new articles. That’s changed now, though, and they can get on with their lives.

I suggest that you get [on with] a life too.

noway said: “You’re an idiot. He had a “breakdown” (aka killing yourself because you’re a dumbass and it’s over) AFTER they had already lost. “

He went insane with power, even taking control of the entire military himself BEFORE losing. That is what CAUSED the loss, well…a portion of the cause anyway. Another big cause was a good chunk of the world whooping their butts.

If you can’t admit that the German war machine was an incredible one and a very powerful and intelligent enemy then you sir, are the idiot. How long did it take the ‘Allies’ to defeat a single country? It’s not like this current Iraq debacle…this was military fighting military. And they were strong enough to conquer a huge region and put up quite the fight for a long time.

If you call Hitler a “dumbass” and truly mean it as a slant at his intellect, I can’t imagine what you must use to refer to George ‘Dubya’!

Sorry to stray off topic, but I’m just reading a story in Popular Science about the F-35B variant of the Joint Strike Fighter.

Range: 450 nautical miles

Weapons: Two 1,000 lb bombs, two air-to-air missiles, 4-barrel Gatling cannon

Cost: $110 million each

Maybe it’s just me, but this doesn’t sound like much bang for the buck. 200 miles in, diddle around, 200 miles out, to deliver two bombs at over $100 million a plane? Ouch.

Jeffrey93 said: “The Avro Arrow made it an easy assumption, that if it weren’t for moronic politicians cancelling the program and scrapping all the finished aircraft, that Canada would have easily been the leader in jet fighter manufacturing for quite some time. At least a lot of the engineers and design team went on to produce other aircraft for other companies, thus making the Arrow somewhat beneficial.

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/6/6b/AvroArrow1.jpg/300px-AvroArrow1.jpg

http://www.exn.ca/news/images/a/arrow-203ongroundbig.jpg

Mach 2.5 Combat speed

Mach 1.0 Cruising speed

Ceiling of nearly 70,000

It was an impressive bird considering this was in the 1950’s, too bad foolish politicians had to get in the way and bugger it all up!”

Wargammer said: “sorry, but speed does not make a good fighter

it does make a good interceptor

the F-16 and F-18 are great because they can out turn anything.

that and pilot awareness are what make great fighters.”

Fighter…interceptor…whatever. It was supposed to be used by Canada/US to defend the north from the Russians. It was a heck of a plane given the time frame.

My comment was in no way insulting Alan or this website (okay, maybe it was a little rude to call it lame–sorry Alan), nor was it expressing a sense of entitlement. I know all about the book, I just didn’t want the site to go to crap because of the book–that would be sadly ironic. I was simply expressing frustration because I miss the “good old days” of having a new article every day. Now it goes 3 or 4 days between articles. However, I forgot to take into account the readers with a chip on their shoulder just waiting for someone to say something they can get angry at, so they can chew them out.

Hmm… maybe a good idea for a future article would be the way that the apparent “anonymity” of the internet makes people disregard all sense of politeness and respect for others. It seems that there are a lot of people that talk big when they can hide behind a screen name, and are quick to jump on other people and insult them with next to no provocation.

Is this their inner persona coming out when it finally has a medium in which to express itself, with little to no chance of consequence/punishment? Or perhaps these people are just jerks in real life as well, and have found yet another way to misbehave, now that the internet is around.

Didn’t your mom ever teach you any manners?

@JM: you are the perfect illustration of the exaggerated sense of entitlement many people seem to have these days. do you really think Allan and his gang OWE you something? they write articles to amuse you, for free, without ads, and you’re bitching about it? jesus. if you don’t like the site, then go read elsewhere.

@Allan B.: maybe the psychology of bitchy over-entitlement would make a good future article. :)

…

Mr. Bellows & Co. have been preoccupied with the preparations for a book of DI articles, as you would know if you’ve been reading carefully. They’ve been really busy and haven’t had as much time as they’d like for new articles. That’s changed now, though, and they can get on with their lives.

I suggest that you get [on with] a life too.

A little forceful, guys, don’t you think? (You could have expressed the exact same ideas without coming off as a jerk/bully.)

…”Had it not been for the shortage of patience and imagination on the part of military officials in the 1960s, we might all be hovering around in our Avrowagons today…”

BUT…as Buzz Lightyear would have said…”To Infinity and Beyond!”

Also note that this article isnt a rerun.

Wolfie said: “Damn Interesting article but I felt I had to defend the British built Harrier after all its not often we Brits manage to lead the world on something!! (other than Concorde (nod to the French as well) and Lynx the only helicoptor capable of flying upside down!). The Harrier is still unique in the fact that it is the only jet aeroplane in the world capable of reverse flight (admittedly not much use in combat) and true vertical takeoff…

On a last note I wonder whether the Joint Strike Fighter will be able to take a bow after delivering its payload?

(BTW. I usually make a point of not getting attached to military aircraft but I was overawed as a child when I saw two of these beasts nod to to the crowd at Cosford air show)”

Yes, that was what I commented on. I still remember that awe inspiring site. It is a shame about the tech difficulties. I would love to see an upside down copter (uh, in the air I mean, lol). Thank you for the cool inf.!

Great article (as always)!

A couple of additional pictures are at http://strangecosmos.com/content/item/123475.html.

djsteiniii said: “Great article (as always)!

A couple of additional pictures are at http://strangecosmos.com/content/item/123475.html.”

Oops, sorry but these are fake. This is a doctored photo of NACA test pilot Scott Crossfield posing in front of a D-558-2 Skyrocket with the crew, the drop carrier, and chase aircraft that supported his record-setting flight. The large saucer replaced the drop carrier aircraft (a conventional fixed wing aircraft with four prop motors) and the smaller saucer replaced his D-558-2 Skyrocket (an experimental rocket craft used to test Mach speeds).

The second picture of a saucer in flight is once again the D-558-2 replaced by the saucer while the F-86 Sabre chase plane is left alone to “Legitimize” said photo.

Untouched photos are cira 1950’s.

Radiatidon said: “Oops, sorry but these are fake. This is a doctored photo of NACA test pilot Scott Crossfield posing in front of a D-558-2 Skyrocket with the crew, the drop carrier, and chase aircraft that supported his record-setting flight. The large saucer replaced the drop carrier aircraft (a conventional fixed wing aircraft with four prop motors) and the smaller saucer replaced his D-558-2 Skyrocket (an experimental rocket craft used to test Mach speeds).

Thanks. But Im surprised anyone would think these where real to begin with, since they absolutely don’t look real. Can’t other people tell fake from real when they first see it? The human vision evolved to tell when there is something weird going on, like say, a tiger trying to hide in the bushes. I would think recognizing a fake picture of a giant saucer at first sight wouldn’t be too difficult.

Q said: “My hovercraft is full of eels!”

Sounds like a great sequel. Has Samuel L. Jackson signed on yet?

Just another little bit of extra info. The word from some people is the whole Avro Air car was to cover up the existance of real, possibly extraterrestrial, flying saucers. So if anyone ever saw one the military could just explain it away as one of ours. Unfortunatly for them the Avro air cars performance was not as good as the Arrow and no where close to the report 5000 plus miles per hour of UFO’s

http://www.ovalecotech.ca

I think we will all see the truth come out about ufo’s and et’s in the next 5 years if the freedom of info act and the time since things have occured is not changed it will be public knowledge. Finaaly the doubters will have to be believers.

Q said: “My hovercraft is full of eels!”

:D fellow python fan…why dont we go back to my place bouncy bouncy…ill give you a good price

Dr. Evil said: “:D fellow python fan…why dont we go back to my place bouncy bouncy…ill give you a good price”

oops…i got my quote wrong…oh well…I will not buy this record, it is scratched.

Dr. Evil is a gay name not like a drug name like mine. Haha he probably likes men. I am a dumb frat boy who likes to shop at hollister.

CCC said: “Dr. Evil is a gay name

As if there could be any such thing…

I am a dumb frat boy”

No argument there!

CCC said: “Dr. Evil is a gay name not like a drug name like mine. Haha he probably likes men. I am a dumb frat boy who likes to shop at hollister.”

hmmm…i guess when u wrote ur homosexual comment about peoples names u were tripping on ccc…now the only reason i could imagine you disliking my name is becoz u wanted ur name to be Dr. Evil, and found that it was taken to u had to replace it with your gay drug name…people like you are the ones that deserve to be beaten with dead cats, but i think ur probably into kinky stuff like that with your dad.

now, instead of sitting at home high as heavens on shit like ccc and spending ur time making uneducated comments such as your, might i suggest you go and find something better to do with your time.

Have an adequate day

Why do some people have problems with the appropriate usage of the words, ‘were’, ‘where’ and ‘we’re’? I’ve noticed this mostly with Brits; is it due to verbal pronunciation similarities and people that write as they speak rather than using proper English?

The Avro Aircar presently in the Smithsonian was a wind tunnel version. The one previously on display at Ft. Eustis Virginia was the one that flew. It was not a “real life flying saucer”, it was a ground effect vehicle — a hovercraft. If not for AVRO’s insistence that it didn’t need a skirt, it would have made a successful hovercraft design. The one in the Smithsonian is in storage in building 22 and is in poor repair, particulary surface corrosion. The Ft. Eustis craft has been disassembled and the parts are in storage for much the same reason (even more corrosion; it was a mere mile from the ocean). A third, wooden version exists in Canada. A fourth 1:5 scale model was built owned by Bill Zuk, who wrote the book about the Avrocar. There is presently a proposal being considered to renovate one or both. Mr. Zuk will be presenting it to the remaining AVRO ex-employees to come to the 60th anniversary of the maiden flight of the CF-105 Arrow, on March 29th, 2008. No Nazis, no top secret transportation arrangements, no such goofy stuff at all. If anyone doubts this, feel free to ask the attendees, who after that cancellation of all their excellent projects have little reason to make up stories about their work. The one 20/20 hindsight issue that would have made all the difference: the rotational precession of the craft was due to the free-flight of the craft attempting to rotate against the rotation of the turbofan. Counter-rotating turbofans would have made all the difference. If, as we hope, we get to transport #2 to the Smithsonian to rebuild and refurbish alongside #1, it is certain discussion will ensue regarding rebuilding and counter-rotating turbofans.

Enter your reply text here. OK

nothing like the left hand substituting for the right hand. Still gets the job done. The penis does not know the difference!

That’s what they said about moterized cars.

Enter your reply text here. OK

This concept does work. Enough money, time, effort can get it done.

hello, it works, but still needs powerful engines too…

Anyone else wondering what we now have that does work and is being hidden away until it is needed? Such as anti-gravity, maybe?

And I also wonder what’s really going on in Provo, Utah.

Still wondering.

Checking back in.

Checking back.

Only 10 days later? I like it.