© 2005 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://www.damninteresting.com/bitten-by-the-nuclear-dragon/?utm_source=DamnInteresting

After the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, the US Army Air Force was preparing to drop a third such bomb if the government of Japan refused to surrender. Manhattan Project scientists had a plutonium core ready to install in another “Fat Man” style atomic device. On 15 August 1945, however, Japan’s Emperor Hirohito announced his country’s unconditional surrender, and the third bomb was never built.

After the war, a few of the Manhattan Project scientists remained on duty at Los Alamos to further explore the behaviors and potential of nuclear technology. Among them was Dr. Louis Slotin, who in his own words was kept around because he was “one of the few people left here who are experienced bomb putter-togetherers.”

During his time there, one of Dr. Slotin’s duties was to use the undeployed plutonium core to perform criticality tests. The tests required him to lower a dome of beryllium, a neutron reflector, over the radioactive material, and measure the beginnings of the fission reaction. This way, scientists could indirectly determine the critical mass of the material without actually starting a nuclear chain reaction. It was necessary to leave a gap between the two halves of the beryllium shell, otherwise a dangerous reaction would occur. Slotin’s preferred method of maintaining this gap was an ordinary screwdriver. He had a strong distrust of automated safety systems.

Dr. Richard Feynman, a fellow Los Alamos scientist, had remarked that these criticality tests were “tickling the tail of a sleeping dragon,” because they brought the fissile materials so close to a dangerous critical state. In fact, another physicist at Los Alamos, Harry K. Daghlian, had been injured by radiation exposure during a criticality test just nine months earlier, when he accidentally dropped a brick of tungsten carbide onto the plutonium sphere. Tungsten carbide is a neutron reflector, which decreases the amount of nuclear material needed to go critical. In Daghlian’s case, it caused the plutonium mass to bathe him in neutron and gamma radiation. He soon collapsed from the acute radiation poisoning. He died less than a month later.

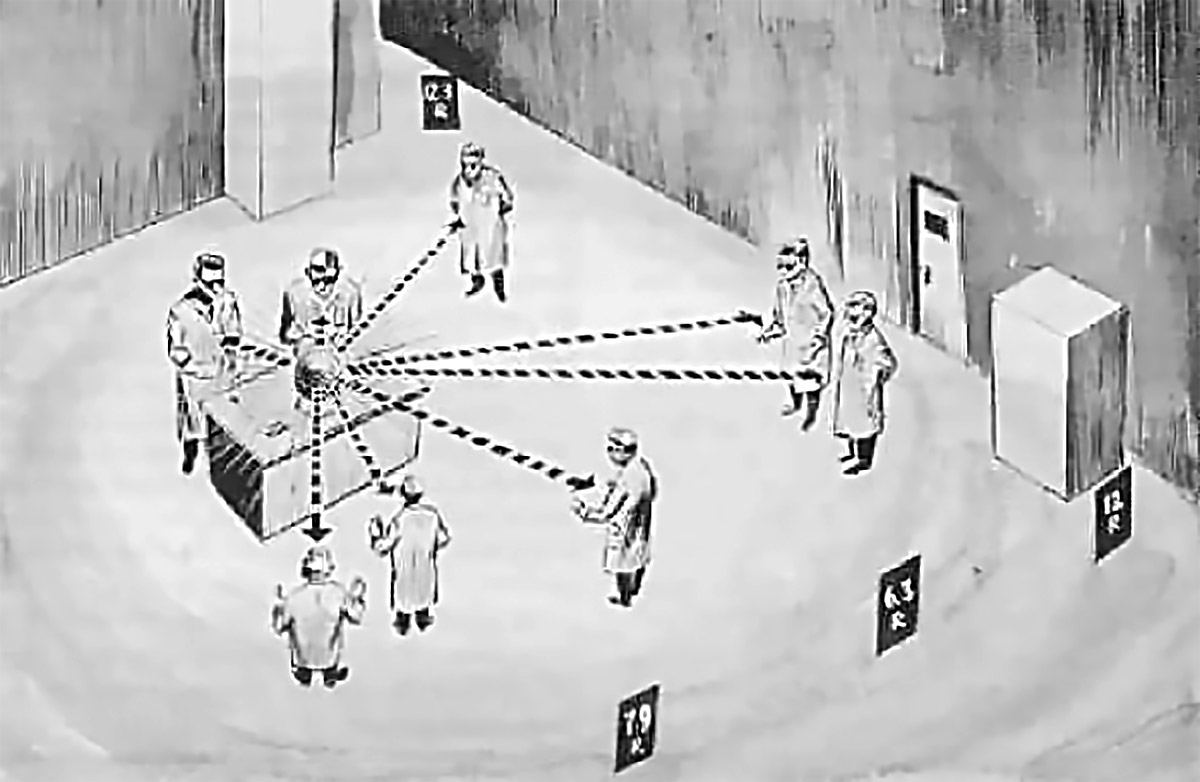

Louis Slotin’s experiment of 21 May 1946 didn’t involve such neutron reflecting bricks, but it did utilize the same plutonium core as Daghlian’s experiment. At the secret Omega Site Laboratory, as six observers looked on, Slotin was training a colleague who was meant to replace him, one Alvin C. Graves. Slotin gently lowered the beryllium dome over the sphere of plutonium, using his screwdriver to maintain the gap so neutrons could escape safely. The screwdriver slipped, and the dome fell to fully cover the core.

Immediately, all eight scientists in the room felt a wave of heat accompanied by a blue flash as the plutonium sphere vomited an invisible burst of gamma and neutron radiation into the room. As the lab’s Geiger counter clicked hysterically, Slotin used his bare hand to push the beryllium dome off and onto the floor, which terminated the prompt critical reaction moments after it began. “Well,” Slotin said gravely, “that does it.”

Slotin, having been closest to the event, soon complained of a painful burning sensation in his left hand, and a sour taste in his mouth. His colleagues rushed him outside and into a car bound for the hospital, but he had already begun vomiting, a sign of acute radiation poisoning. The other scientists who had been in the room didn’t experience any immediate symptoms, indicating that Slotin’s reflex to swat away the dome had spared them from a similar level of exposure. All too familiar with the consequences of such a powerful dose of radiation, he said to his colleagues in the car, “You’ll be OK, but I think I’m done for.” After arriving at the Los Alamos hospital, Slotin said to Alvin Graves, “I’m sorry I got you into this. I’m afraid I have less than a 50 percent chance of living. I hope you have better than that.”

He had a telegram sent to his parents in Winnipeg to inform them of the accident, and a few days later, he telephoned them with the assistance of a nurse who held the receiver for him. Major-General Leslie R. Groves, the administrator of the Manhattan Project, sent a U.S. Army DC-3 to pick up his parents, and they arrived just days before he would die of radiation exposure. As Slotin awaited the inevitable, the Los Alamos authorities issued a special citation, which was read to him in the hospital:

Dr. Slotin’s quick reaction at the immediate risk of his own life prevented a more serious development of the experiment which would certainly have resulted in the death of the seven men working with him, as well as serious injury to others in the general vicinity.

He died nine days after the incident.

Louis Slotin is generally regarded as a hero for his quick, selfless action to end the reaction with his bare hand, but the true tragedy is that the entire accident could have been avoided with some simple safety precautions. A better method would have been to raise the beryllium dome from below the core on a levered mechanism—in the event of a slip with such an assembly, the dome would fall harmlessly down and away instead of into the dangerous prompt critical position. Slotin also neglected to use two safety spacers which had been developed after his colleague was killed by the same core nine months earlier. Louis Slotin saved the immediate lives of some colleagues, but his neglect of safety protocols is what created the danger in the first place.

Within the next couple of years, two of the scientists who had been observing the experiment died with symptoms of radiation sickness.

A previous version of this article incorrectly described the demonstration as using two hemispheres of plutonium rather than two halves of a beryllium neutron shield.

© 2005 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://www.damninteresting.com/bitten-by-the-nuclear-dragon/?utm_source=DamnInteresting

Since you enjoyed our work enough to print it out, and read it clear to the end, would you consider donating a few dollars at https://www.damninteresting.com/donate ?

This type of thing baffles me. I suppose that many lessons are learned through mistakes such as these, but you would think that when it comes to experimenting with nuclear materials more precaution would be taken than a mere couple of screwdrivers and some steady hands.

I am sure there are countless fatal errors such as this that are all but unknown. Even outside of that it is already very apparent some of the ill-fated results of nuclear fallout and exposure to citizens in this country due to nuclear testing in the Nevada desert.

I always find this fascinating to learn of such things. A friend of mine who attended nuclear energy school for the US Navy often commented on case studies or accidents that they were precautioned about due to highly radioactive nuclear materials… in one story he shared an incident in which some nuclear material no bigger than a marble caused paint to peel off of a wall and curl all the way to the ceiling. In another the gov’t experimented and found that exposure of materials would turn glass a dark, almost black color when in near contact to similar materials.

I guess the disturbing thing is that people actually engaged in this and that there were such lessons learned. As I have read about the effects of radiation poisoning I realize that many of these symptoms are know as a direct results of people witnessing and being exposed to radioactive materials.

“Slotin’s preferred method of keeping the two hemispheres separated was an ordinary screwdriver, because he had a strong distrust of automated safety systems.”

So… why did he distrust those systems so much?

I don’t care what you say, it takes a hard-core scientist to grab a reacting chunk of plutonium the size of half a bowling ball.

Stupid mistake, but heroic.

Rain said,

“I don’t care what you say, it takes a hard-core scientist to grab a reacting chunk of plutonium the size of half a bowling ball.

Stupid mistake, but heroic.”

How do you call something heroic when it didn’t succeed in preventing the catastrophe the ‘hero’ caused by his own actions? He refused to even use the safety spacers! Sounds like a goddamn cowboy to me. He succeeded in killing himself and two other people with his cowboy tactics that he justified by a ‘distrust of automated safety systems’. Pathetic, truly pathetic. ‘Scientists’ like this give the field a bad name.

Just a minor point, but I suspect all of the commentary so far has come from people who weren’t even born when these events took place and probably haven’t a clue about the zeitgeist of those times, the fallability of ANY automated system in those days, etc. etc. My personal reaction is that similar bravery and rapid action that involves and disregards self-survival was rare then and is moreso today. And dismissing such as “stupid” or “pathetic” is, at best, vapid arrogance and disrespect from some pretty narcissistic people who doubtless couldn’t appreciate a black-and-white movie or TV show if their lives depended on it…and back then, when they made the telephone calls, the parents may well have answered on a hand-crank wall phone.

For a complete list of criticality accidents from US/USSR/UK/Japan, check out this pdf. The wikipedia article has a condensed list.

It’s surprising to see how many of these accidents are caused by operator error and poor judgement.

Thanks Sparky, for that pdf.

I was in danger of sleeping well tonight!

Familiarity breeds contempt. I got dangerously close to electrocuting myself a few times when working as a radio engineer, simply because the precautions were a bit of a pain, and I just needed to run a “quick check”.

The gravity-based fail safe system described above would have prevented this disaster however, and since it appears that they repeated this test frequently, it would have been a lifesaver. Literally.

Slotin used a screwdriver. A screwdriver. There WAS an automated safety system, but no, he didn’t use it. Didn’t want to use it. He could have used the safety spacers, but he didn’t use them either. No, he used a screwdriver. Even with the safety equipment, the test was dangerous and would have dosed the scientists with a massive amount of radiation. Slotin went one step further and used a screwdriver. It’s like someone driving really fast, and not using a helmet.

In regards to his actions on that day, he did save a lot of people, but he, undeniably, caused the accident in the first place. And who was he really trying to save? Was he thinking about his comrades, or merely himself? He was closest to the half spheres, and he might have pushed it away out of a fear reflex. I don’t think we can say with any certainty that he was a hero. It’s not like he rushed from the other side of the room, charging like a hero to stop the reaction. He was right in front of it, and he pushed the half sphere away to stop it. Reflex or heroic act? I don’t know. But we do know it was his fault he and two other co-workers died and the rest got seriously ill.

Cornerpocket, I’m 44 years old. Is that old enough to appreciate the ‘zeitgeist’ of that era? I grew up with black-and-white tv but I don’t remember Kennedy’s assassination. Being younger than you doesn’t mean I don’t recognize sheer stupidity when I see it. And you know what else? I’d rather be vapidly arrogant, narcissistic and disrespectful than jeopardize the lives of myself and others around me by not BOTHERING to use the safety systems that WERE AVAILABLE to Slotin….he couldn’t even be bothered to place some simple shims in place! In refusing to do so he killed himself and two others.

I wouldn’t have called Slotin’s actions ‘stupid’ or ‘pathetic’ if I’d been able to think of more perjorative adjectives. Those words are totally inadequate descriptions of the magnitude of the idiocy.

To me, not using the safety systems when there is NO REASON NOT TO is not only criminally negligent, it’s absurdly arrogant, showboating (narcissism), and utterly disrespectful of his own and others’ safety. You threw those last three descriptions my way very quickly without ever having met me, but nobody who knows me at all would ever accuse me of any of those things. They’re far more applicable to the man whose stupidity you defended.

If you’re holding that kind of action up as an example of the ‘zeitgeist’ of the era, I’m more amazed than ever that we didn’t succeed in exterminating ourselves from this planet.

This incident happened in 1946, are you telling me, Cornerpocket, that you are old enough to appreciate the fallability of safety systems of that year?

I don’t claim to be old enough to have experience, but I’m fairly sure that health and safety wasnt then the issue it is now. These were days when mains voltage fuse boxes were checked by licking your fingers and running them down the terminals.

While his actions may have been negligent, it was his experiment, and he may well have felt safer using a method of his own (which he had been using successfully for some time) rather than some new method given to him, possibly by someone without his experience. People do things how they feel safe – we’re not objective. Also, if his colleagues were worried, surely they would have said something or not been there at the time.

As for whether his actions were heroic, I reckon I’d be running. It wouldn’t help me in the slightest, but that’s the reaction. I’d like to think that I’d have the calmness of mind to separate the hemispheres, but I’m not sure I would. Even if he was just fixing his own mistake, it’s better than making a mistake and leaving it to kill your colleagues.

Nastimann said: “Familiarity breeds contempt. I got dangerously close to electrocuting myself a few times when working as a radio engineer, simply because the precautions were a bit of a pain, and I just needed to run a “quick check.”

I think this succinctly sums up the attitude in many places, and unfortunately it’s much more common than it should be. No place is immune, as evidenced by the NASA shuttles being destroyed. Heck, even I’ve been guilty of it. It’s a problem that requires a very forceful and dictator-like management to solve, since people by themselves won’t resolve it. For example, where I work, if you caught violating any portion of the safety procedure, you will get your keys to the lab confiscated immediately. Another violation afterwards is being barred for a few weeks. For someone who needs experiments done on a deadline, this is incredibly damaging.

I can sympathize… in plenty of of situations, it’s sure hard to figure out the “do” and “don’t do” when everyone around you (including supervisors) is saying one thing and doing another, and where the book might say “don’t use a screwdriver” but you worry that everyone around you thinks you’re a bit of a wuss if you’re the only one to follow written protocol. (I’m just getting started, but already I’ve seen colleages drag-netting on foot in four feet of muddy water in saltwater crocodile territory, or refusing to put on an ace bandage after a snakebite, or skipping out on reporting injuries… maybe it’s a question of people not admitting the risks they take. Hey, data is data, and who wants to forgo that?)

Not condoning Slotin–I think that was a terrifically stupid, negligent, and reprehensible thing to do, sort of like drunk driving–but I reckon this makes a good lesson for fellow labgoers out there to stick to what you KNOW to be safe and correct and not yield to peer pressure or macho man syndrome.

You people are beyond clueless. These guys were operating on edge of the technological envelope, and were under intense pressure to produce results, quickly. Safety was a secondary consideration.

Also, consider that nuclear research was Top Secret and much of the information about it was compartmentalized. Most of the people in that room were probably not very cognizant of nuclear safety — because nobody had really looked at it as an issue before.

The cowboy attitude towards nuclear devices and materials ended when Admiral Rickover was put in charge of the Navy’s nuclear program after a submarine sunk due to a reactor safety issue. Fanatical attention to detail and safety then became “priority one” and the Navy hasn’t had a single incident since.

No one’s made this incredibly bad (and ironic) pun yet, so I guess I have to do the honors:

When the screwdriver slipped and the two masses came together, Dr. Slotin was screwed.

Joshua: ouch! Now I’m annoyed I didn’t think of it. You win – Nice!

This accident was depicted in a movie called “Fat Man and Little Boy”, a forgettable, smarmy film that starred Paul Newman as Leslie Groves and some guy I don’t recall as Oppenheimer. The scene where the two halves of material come together was shot with fairly artistic paucity – the scientist was portrayed by John Cusak: the screwdriver slipped, stuff sparked and flashed, and the next several scenes show him bloating, rotting, bleeding, and suffering hugely. It was a very disquieting bit of film, regardless I didn’t enjoy much else of the movie, and now I see that the timeline was all wrong – the scene, obviously a nod to Slotkin, was depicted as occurring before the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs were even built.

In 2006, we marvel at our phenomenal grasp of science and ingenuity, begat without animal testing and in the electronic world of supercomputing, and based upon the ragged experimental lunacy of our forefathers. In 1946 this guy was separated from enough fissile material to cause significant mayhem by some sandbags and boards. Nobody knew a hell of a lot about this radioactivity stuff, not like we do today. The screwdriver slipped. Lives were lost. THAT doesn’t happen at Lawrence Livermore or Sandia nowadays, now does it? Of course, the development cycles today for dangerous stuff are MUCH longer than the turnaround asked for by the Truman administration regarding the bomb.

So… Icarus and Daedalus went for a little flight once (a little mythological license needed here). Neither knew much about flight, not like we do today. All that supported them was some leather straps and some wax. Lives were lost.

And…some soldiers hopped into a homemade submarine called the Hunley once. None of them knew much about submarines, not like we do today. All that protected them was a lot of hammered, riveted steel and wood. Lives were lost.

Hmm. I’m not smart enough to wax philosophically. Point is – the bomb, military submarines, and flight required some pretty incredible risks, and – historically – scientifically-minded types like to break the rules, don’t they?

Me? I’m a big puss. I wear a helmet when I ride, keep a spare key hidden, and am a firm believer in condoms. I could never have invented stuff in the old days…even as recently as 1946.

Hero? Yes.

Pathetic? Then, no. If it happened today, yes.

The world of 1946 was vastly different than the way we operate today – back then most people were cutting seat belts out of cars and pumping gas while smoking. Surgeons regularly performed procedures with a Marlboro between their lips (my grandfather was an anesthesiologist, I’ve heard the stories about how he had to deal with that type of thing). Nuclear science was not known as well as it is today, and as far as the state of the art in nuclear testing went, Slotkin was one of the most knowledgeable people in the world. You cannot judge people back then working onthe bleeding edge of the science by the safety standards of today. Sure, 2 other people died years later from it, but there were another 4 people in that room that survived without the complications of radiation sickness because he took action right away. Do you judge a hero by the lives he failed to save, or the lives that he did save?

Today we are a lot more concious of safety, in part because we have things that can kill you with much less warning than back then. Cars didn’t regularly do 80 MPH on the freeways then, closer to 50 – much more warning of a collision with cars and people then than now. You could get out of the way. Safety procedures they had then were not as effective as we have now… how many carpenters from that era had at most 9 fingers, as compared with today?

Safety is a big part of our lives today becuase we recognize how it can save many lives. Back then, it was just a matter of getting the job done.

Regardless of how little we knew then or how much we know now, Slotkin had to be quite aware of the amount of energy that would be released if anything went wrong. He was also quite aware of what happened to people who were exposed to that energy in large doses. High energy is dangerous –period — whether it is chemical, electrical, mechanical or nuclear.

I think the biggest difference between now and then is that we have become far more risk-averse, and we have nurtured the victim mentality with huge legal settlements when something does go wrong.

Scredrivers and a lack of safeties – all I need to hear about now is duct tape….

Being from the south…. I use Duct Tape as my standard safety system. Last words? “Hey guys, watch this!”

In this reply, I didn’t even have to look up and use any long words to make myself seem schooled.

Semper Fidelis

now see heres what i think. i think that he was right to not use safety equipment just because it can fail at any moment like if they used hydrolics to lift the bottom one up to the top one then what if a switch went bad? i disagree with him not useing spacers though.

Having found this site only recently, I’m glad your running some older articles. Really great stuff on this site.

This has to be one of the ultimate “Holy Crap” kind of days for those guys.

Have a look at that first picture. It says all that needs to be said about the lack of knowledge at the time about the dangers of radiation – Those two hemispheres are at crotch-height.

cornerpocket said: “Just a minor point, but I suspect all of the commentary so far has come from people who weren’t even born when these events took place and probably haven’t a clue about the zeitgeist of those times, the fallability of ANY automated system in those days, etc. etc. “

Safty spacers aren’t automated, they’re a sensible precaution.The person who you’re critisizing makes a good point he endangered life needlessly.

I watched “Fat Man and Little Boy” in eighth grade science class. I thought the experiment in the movie was meant to be Daghlian, but they deffinitely made an error with the two hemispheres rather than the brick of tungsten carbide. Anyway, as far as I know Slotin and Daghlian worked closely together on tests like this. Slotin really should have known better than to do the experiment this way.

As a firefighter I can assure you that (at least for that profession) most quote unquote brave/heroic actions are the result of 1) reflex action and 2) stupidity that somehow works out alright. Brave/heroic actions do not come from rational thought, you don’t think it through you just do it — and a lot of it has as much to do (if not more) with self preservation than it does the preservation of neighbor.

Concerning Dr. Slotin’s use of a screwdriver… well it was his preferred method and the exact reasons why are lost. It doesn’t seem like a sound method to me yet, what these people were doing is not really what I’d consider sound thinking anyway. Then again, many people would consider running (well we don’t run we crawl) into a burning building not the actions of a sound thinking either.

tom

How is a hand-held screwdriver less fallible than a simple mechanical device?

Might as well test napalm by standing in a vat of it and flicking matches…

And these were the $500 special government screwdrivers too!

No, they were only $450 because he returned the spacers for store credit.

foxy said: “How is a hand-held screwdriver less fallible than a simple mechanical device?

Might as well test napalm by standing in a vat of it and flicking matches…”

Without knowing the man or equipment he used, it is foolish to judge him as either innocent or guilty depending on your viewpoint.

Having worked in various lab-based and on-site based situations, I can testify that sometimes the safety equipment is more dangerous in use that without.

During a visual alignment of a HE/NE laser setup, the safety failed and “zapped” my eye. Thankfully this was a low-power experiment and all I suffered was temporary blindness for a few hours. Normally I used a simple cardboard and clay block during alignment, but the powers-that-be made me use the safety system instead. They said it looked more professional than my “Mickey Mouse Contraption”.

During another experiment with a high-power CO2 laser, the safety override failed when I was “in-target”. Thankfully the focusing unit was not calibrated at that time and all I received was a three-second burn across my chest before I leaped out-of-beam. I did suffer a second-degree burn from this. Since the targeting system required the main laser to operate, the laser had to be fully powered up. Normally I used a penlight with focusing array to pre-setup and calibrate the laser. Once again the powers-that-be told me to quit being a ninny and use the pre-setup built into the laser.

While doing some high work at a Nuclear Facility, we were required to “tie-off” our safety belt rope to the scaffolding. There were no safety guide wires to tie-off at the work location. I argued that was more dangerous than not having the men tied-off. I lost. A man lost his grip and fell; of course his weight also took the scaffolding off balance. Due to his required tie-off, instead of a single man getting hurt, four others joined him in the hospital. All five had been on the scaffolding with the accident occurred. Three were hurt more severely when the metal scaffolding fell on top of them.

So once again it all depends on the circumstances.

I too work in a lab (with lasers and nasty chemicals) and I agree with Radiation (above) that those wondering why he used a screwdriver are jumping to conclusions. There are times, particularly when handling dangerous stuff, that the operator wants to be in as much direct control of the situation as possible. I *never* use a funnel when filling filling a container with acid, for example. You start to lose respect and get sloppy. Using a screwdriver would provide instant feed back about the position, rate of movement, slipping, etc of the hemisphere. As for the spacers, if the spacers were there to prevent the hemispheres from contacting, and the experiment was to bring the hemispheres into contact…well that’s like trying using the laser safety glasses when trying to align the beam.

No consequential development of superpowers?

The same kind of thing happened with Chernobyl. Lake of safety protocol and an “Experienced” operator who took short cuts caused that tragedy.

Meant to say “Lack”.. sorry it’s late.

I read a mini-biography of this guy Slotin a few years ago, and learned a few things about him as a human being. For one thing he had a reputation among his collegues as being rather impulsive, to the point of even being rash. One scientist (can’t remember name) even refused to be around when Slotin conducted these experiments and even predicted that this is how he would die. Slotin was also considered rather a braggart and fabricator, as he would claim to have flown Spitfire fighters (he WAS a quaified pilot) for the RAF as a Canadian volunteer during the Battle of Britain…even though there was absolutely no record of anyone by his name ever serving with the RAF in any capacity..

A previous letter told us that: “This accident was depicted in a movie called “Fat Man and Little Boy.”

That’s correct, however many years earlier the accident was depicted in “The Beginning or the End”, a film made immediately after the war, probably 1946. It was presented as the story of the A-bomb, but was highly fictionalized. As I recall, Brian Donlevy starred as General Groves.

More recently, a TV documentary was produced specifically about the Slotin incident (Tickling the Dragon’s Tail).

LITERALLY a case of “Hey guys, watch this!” — the audience served no purpose, the so-called experiment was previously completed, and the operator killed himself and harmed others while showing off.

Slotin was, as he noted, the first and definitely the most preeminent “bomb putter-togetherer” in the world at the time. He assembled the world’s first atomic weapon (the Gadget) at Trinity, and then watched it blow up perfectly. That’s the kind of thing that can give a certain kind of man a massive ego. Self-trained experts in any extremely dangerous, cutting-edge field tend to be very gung-ho, individualistic, quasi-suicidal types because that’s who is attracted to that kind of job. Once the job gets figured out properly and the safety manual gets written, all the risk (and excitement, and glory, and adrenaline) goes out of it, and thus these individuals gravitate towards something else death-defying and thrilling.

A lot of the scientists in the Manhattan Project were the same way: twenty-somethings at the top of their class from the preeminent science programs in the world, vastly arrogant and myopic towards their particular field, and not inclined to listen to anybody. Leslie Groves had a bitch of a time trying to enforce various basic military standards on them. It was like trying to herd cats. If they didn’t want to do something they saw as unnecessarily infringing on their glory, they tended to simply ignore it. And once the “build the unbuildable at any cost” Manhattan Project was over and the nuclear weapons labs fell under massive government oversight, 90% of those brave young pioneers ran for low-oversight university research gigs where they could continue to be cutting edge and risky. A number of them were involved in the horrendous human radioisotope experiments that took place in the late 40s and 50s.

TL;DR, Slotin was probably a genius and most certainly a jackass with a malformed sense of self preservation, but those two traits tend to go hand-in-hand most of the time. To expect otherwise is unrealistic.

Anyone know exactly what would have happened if he hadn’t knocked off the top half? Would there have been a mushroom cloud? Do these things really take more than a couple of seconds?

Tharpa, it was never in danger of going supercritical to the point of any kind of blast, it takes special perfectly-shaped explosions pushing the plutonium in on itself crushing it into a tiny ball before that could happen.

When two pre-critical masses like the two halves of the “demon core” are brought together enough to go critical, the heat and energy generated by the first large burst of fissions would force the core halves apart again violently, terminating the reaction.

If Slotin had not reacted as quickly as he did however, everyone in that room would have died and not just him, and possibly there would have been serious contamination of that lab for a long time and some more horrible radiation-related deaths and/or illnesses by the time the reaction self-terminated.

Myself, I thought that “Fat Man and Little Boy” was a good movie.

This article reminds me of the photographs of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki victims.

So far, we’ve kept the dragon fairly well contained, but I don’t know for how much longer.

I had to check back in.

And again – one year plus one day.