© 2020 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://www.damninteresting.com/curio/signs-and-space/

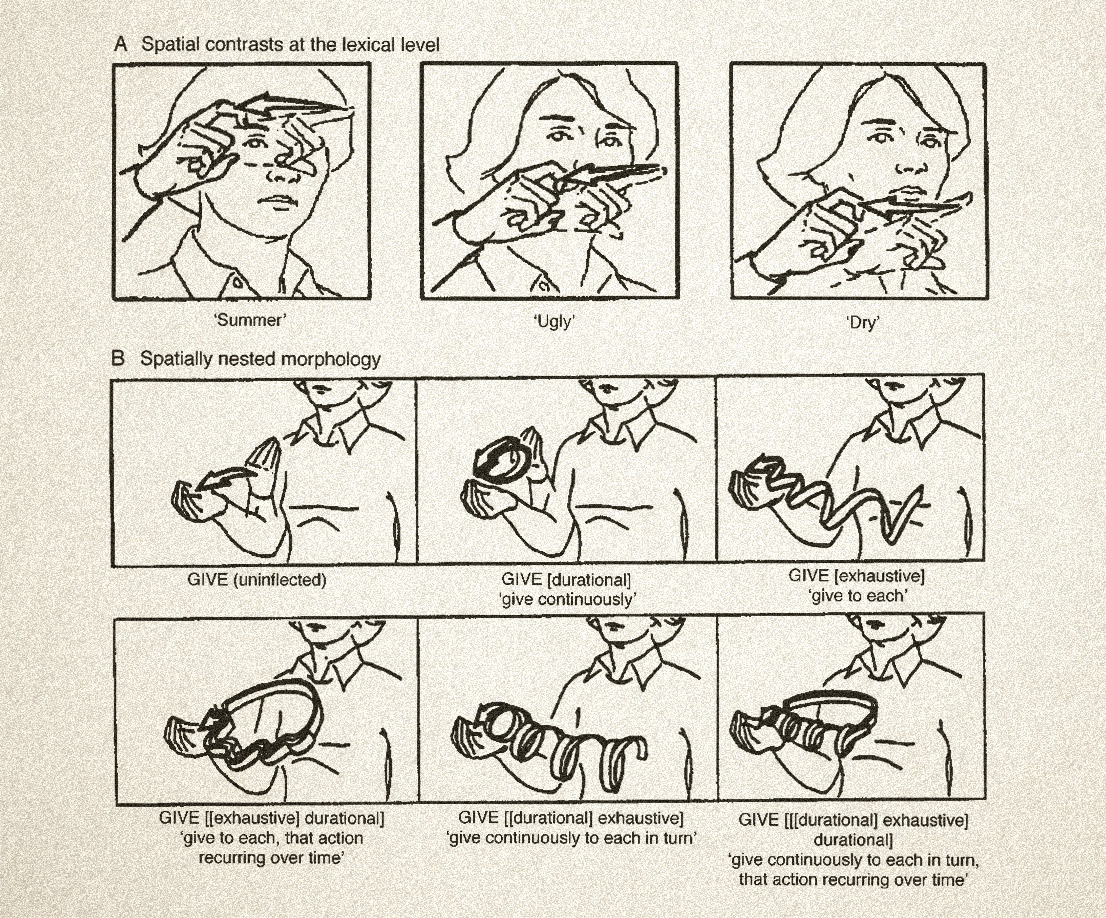

Sign languages rely on the use of space (locations, motions, and handshapes) to express meaning or grammatical nuance, or both. This use of space for the sake of language is neurologically distinct from spatial processing in general; in fact, it appears to be located in the opposite hemisphere of the brain.

A team of California researchers found in 1998 that native signers with damage to particular regions of their left hemispheres had impaired use of space for grammatical purposes, but could draw and copy diagrams normally. Conversely, native signers with right-hemisphere damage could not copy drawings well, but their use of space in their signing was entirely intact. The key appears to be that the primary language-areas of the brain are localized to the left hemisphere regardless of whether the language being processed is auditory or visual.

© 2020 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://www.damninteresting.com/curio/signs-and-space/

Since you enjoyed our work enough to print it out, and read it clear to the end, would you consider donating a few dollars at https://www.damninteresting.com/donate ?

This is in keeping with several students whom I had over the years who had brain damage in the left hemisphere. However, they were not signers; they were speakers. Still, they exhibited the same tendencies.

I signed and ended up with a huge migraine in a specific spot of my brain. It was in the front, I don’t remember which side. So it does use a dormant section of brain or at least over exerts a section of brain.