© 2017 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://www.damninteresting.com/no-country-for-ye-olde-men/

The year was 1721. The ship was called the Prince Royal, its destination the American colonies. And the cake—the cake was gingerbread.

The British crew shouldn’t have been surprised to find the metal file in the cake. Its stasher, James Dalton—a notorious thief and escape artist—had been shuttled involuntarily between Britain and America more times than a trans-Atlantic diplomat. Unluckily for Dalton, this particular mutiny fell apart as soon as the cake did. Luckily for Dalton, there would always be a next time. After all, as a convict who’d been sentenced to the punishment of “transportation” multiple times, Dalton had mutinied before.

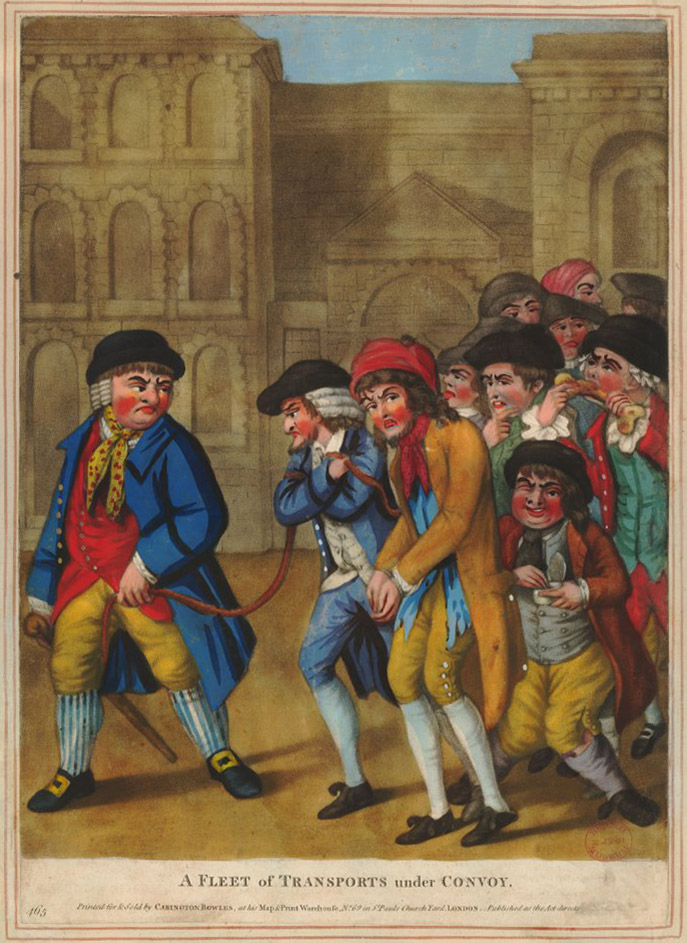

While conditions in 18th-century British prisons could be horrific (more convicts died in prisons than at the gallows), the most feared punishment didn’t take place in prison at all. Between 1718 and 1776, British authorities exiled approximately 50,000 convicts to American colonies in a policy euphemistically known as “transportation.” Once in America, the convicts fell under a life of servitude or outright slavery, underfed and overworked. They had to obey their masters or risk being imprisoned, with punishment including whippings. In the early period of transportation, half of these prisoners died while in bondage.

Unsurprisingly, the policy of transportation wasn’t so popular among British convicts. Some prisoners even begged to be executed rather than shipped abroad. Thus, plenty of prisoners sentenced to transportation attempted to escape partway through the journey. Multiple convict-carrying ships bound for America suffered prisoner rebellions. Rather than heading to remote parts of the colonies upon arrival, most escaped convicts preferred to sneak back to Britain, despite being subject to execution for the meta-crime of returning from transportation.

James Dalton was one such convict. He grew up surrounded by crime and punishment; his father cheated in gambling, and his mother and sister were transported for criminal activity. When Dalton was five years old, his father was executed for robbery—and in an awkward bit of father-son bonding, he smuggled young James into the execution site in the cart that was transporting him to the gallows, so that the boy could watch. Dalton’s own criminal career started at the age of eleven, and according to his later prison memoir this involved an impressively diverse range of misdeeds such as stealing “a parcel of wet Linnen hanging to dry in the Garden” and toys from a toy shop. He ran a London street gang and called himself “one of the most impudent irreclaimable Thieves that ever was in England.” The proceeds from such thefts generally went toward the company of prostitutes. (Dalton’s inveterate womanizing would also ultimately land him in hot water.)

Belying the saying about honor among thieves, Dalton stole from his accomplices, and all testified against each other when caught by the authorities. After one of his former comrades-in-thieving-and-whoring gave Dalton up, he was sentenced to the dreaded transportation.

In May 1720, Dalton was put on board the (ironically named) Honour, bound for Virginia. The felons aboard the ship consisted of 36 men and 20 women. They outnumbered the crew of 12, led by Captain Langley.

Oceanic crossings were prone to severe gusts. “One Day when we were at Sea,” Dalton would later write, “a Gale of Wind arose that blew very hard, and carried away our Main-Top-Mast.” Twelve of the men—including Dalton—agreed to help with the repairs on deck and had their chains removed. The first mate made Dalton steward of the prisoners. Dalton was keenly aware of the provisions brought on board by a fellow prisoner, Hescot: “about fifty Pound of Bisket, two Caggs of Geneva [gin], a Cheese and some Butter.” Dalton and his prisoner buddies proceeded to take the food and liquor for themselves. Hescot complained to Captain Langley, who threatened to whip all of the prisoners to find the culprit. But before he could do so, Dalton gave the prearranged signal. He and 14 other felons seized the ship’s weapons, immobilized the 12 crew members, and took control of the vessel.

As mutinies go, it was a relatively civilized one. One prisoner who had refused to go along with the uprising changed his mind once the mutiny was complete. Dalton and his co-conspirators granted the turncoat his freedom in exchange for £10. They even provided him with a receipt.

The mutineers held control for 14 days. Near Cape Finisterre, Spain, the mutineers relieved the captain and first mate of their watches, money, and other possessions, amounting to about £100 in value. They compelled sailors to bring the long boat around. Then the merry mutineers shared drinks with the captain and first mate before setting them free. Dalton and his accomplices made off in the long boat and reached the Spanish coast in just a few hours.

From Spain, the escapees headed to Portugal. Dalton and eight others boarded a Dutch man-of-war bound for Amsterdam, where Dalton committed robberies to get back into the swing of things. When he was sufficiently swung, he returned to England. There, he saved enough money from his robberies to marry a wheelbarrow pusher named Mary Tomlin.

However, his line of business caused marital discord. Dalton left his wife to live with another woman—who reported to the authorities that he had returned from transportation. He was detained and brought to Newgate prison under the Transportation Act, where he was tried with other mutineers. All were found guilty and sentenced to death. Their sentences were later commuted to transportation to America for 14 years.

In August 1721, Dalton set sail with the other passengers of the Prince Royal. He had rebellion on his mind again, as demonstrated by a gingerbread cake in his possession that happened to break apart while the convicts boarded. The guards discovered that there was not just cakey goodness inside, but also a file—an early version of the cartoon trope of prisoners breaking out using weapons baked into cakes. Following the foiling of the filing, the crew tied Dalton up and watched him carefully.

This time, Dalton made it to the other side of the Atlantic. But he didn’t stay put for long. Dalton embarked on a cycle of running away, living on foods such as venison and moss, getting caught, running away again, selling horses or slaves, making it back to England, and getting transported—again. While in America, Dalton’s relationships with his masters were never very conciliatory, likely because of his reluctance to treat them as masters. At one point, he noted, “when my Master bid me go to work, I told him Work was intended for Horses and not for Christians.”

Dalton even took one of these trans-Atlantic trips willingly. When facing a charge of returning from transportation, he turned informant on six of his former accomplices to get himself off the hook. While freed, he lived in fear of retaliation by the widows of the former accomplices, whose husbands had been hanged based on his testimony. Thus, using the £40 the government had paid him for his assistance, he chose to travel to Virginia for a period while things in London cooled down.

However, he came to the end that befell most convicts who resisted transportation. Back in Britain, he was put on trial for the highway robbery of John Waller. Dalton denied committing the crime, though he admitted to an abundance of others. He considered Waller a liar and a chronic snitch; Waller was as profuse in testifying against criminal suspects as Dalton was in relieving people of their property.

Although Dalton swore his innocence to the end, he was reported to be “very cheerful” on his way to his execution. In 1730, ten years after he was first sentenced to transportation, Dalton’s body was finally transported underground—via the hangman’s noose.

Two years later, Waller was convicted of perjury, again for an accusation of highway robbery. He was pilloried in a public spot. While he stood bent over with head and hands trapped in the wooden pillory, his brother Edward beat him to death.

As a criminal, Dalton had nine lives. He essentially bullied his masters, refused to work, and engineered more felonious exploits in America. He didn’t die on board multiple ship journeys and he wasn’t immediately executed upon returning to England.

And he was also clearly successful with the ladies. Dalton was as prolific a husband as he was a thief; four of his ex-wives came to see him during one of his stints at Newgate prison, and appeared to be on good terms with each other. At least one of these marriages was strictly business, as she was pregnant and her family paid him to marry her.

As for the practice of transportation to America, it ended with the American Revolution. The pesky Americans’ demands for independence caused Britain to stop sending its convicts to America and to force them to Australia instead. The Australian convict trade wound up about three times as large as the American version.

The smaller scale is just one reason that U.S. history overlooked the fact that some of its long-lineage East Coasters are presumably descended from convicts. Patriotic 19th-century historians asserted the practice was less common than it actually was. Showing that American politicians’ massaging of facts has a long and illustrious history, Thomas Jefferson claimed in “Notes on the State of Virginia” that the number of convicts sent to America as just four percent of the actual figure, and that these people were thankfully kept out of the American gene pool: “I do not think the whole number sent would amount to 2000 & being principally men eaten up with disease, they married seldom & propagated little.”

In Dalton’s case, he certainly stayed true to his path. He achieved a sort of rascally notoriety toward the end of his life with the publication of his memoirs, and his family history led a prison chaplain to later say of Dalton, “One may easily conjecture what Sort of a Tree grows from such a Stock.” Dalton did little to dissuade anyone, much less history, of that conjecture.

© 2017 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://www.damninteresting.com/no-country-for-ye-olde-men/

Since you enjoyed our work enough to print it out, and read it clear to the end, would you consider donating a few dollars at https://www.damninteresting.com/donate ?

Yet another enjoyable read from DI! Thanks.

“While conditions in 18th-century British prisons could be horrific (more convicts died in prisons than at the gallows)”

Some things haven’t changed. In the modern penal system more inmates die in prison than by execution, and in the US that includes the population on death row.

1st/3rd! (No one said 1st?) Good read. I’d love to learn more of how they made it out of servitude and into the American gene pool.

Great work dinosaur Christine Ro!

Great read for sure. We love hearing about rascals like this, all the archtypes like Robin Hood, Ali Baba, Al’Adin, and the real ones like this fellow, The wild west outlaws like Billy the Kid and Jesse James, and those famous Australian Bush-Rangers. I know there’s a long and complex socialogical explanation for this, but I think it boils down to a simple answer.

Such stories are….Damn Interesting!

Many Australians today take a perverse pleasure and pride in claiming descent from convicts, and it’s commonly said that in the early days, “Australians” were hand-picked by the finest judges in England. By the end of transportation, in 1868, more than — not “almost” — three times as many convicts had been shipped to Australia, for what in many cases today look like the most trivial of offences, to some of the worst prisons in the world, although by then, as a paradoxical rule, you were safer being transported at Her Majesty’s pleasure than if you were paying your own way.

The joke, of course, turned out to be on the Brits when Australia, for all its spiders, snakes, crocodiles, sharks, etc. proved itself to be even more benevolent and richer than Br’er Rabbit’s proverbial briar patch; and indeed, they helped so much to build the present country that in at least one heavily ironic case that I can think of, one of Australia’s most lucrative goldfields and thus one of the foundations for the infant country’s early prosperity, was discovered by a discharged, transported felon. More than 1,000,000 ounces of gold was extracted from that discovery alone, only one of many, in only one of many gold-bearing regions. The resulting wealth meant that, for most of the last decades of the 19th century, the state of Victoria alone was the largest export market for British luxury goods, and the sustained tidal wave of hopeful migrants from all over the world quickly diluted the perceived “stain” of convict forebears.

i love the phrase ‘not just cakey goodness inside’. Well done Sauropod!

Nice

“Following the foiling of the filing…”

AAARR-R-R-R-RGH!!… You’ve been around Bellows way too long.

But I liked it! However, as a general rule of prose… Always avoid alliteration!

Enjoyed this. Wished it was longer, of course. And now I wante an article wrytten by ye olde Alan Bellows on the subject of English etymology.

One little complaint. The narrator has strange pronunication of three words I noticed–memoir, impudent, and belying.

Smokey said, “…Always avoid alliteration.” Unless you have a juicy morsel like “Following the foiling of the filing…”, then by all means alliterate away.

Why did the pilloried guy’s brother beat him to death? That sounds damn interesting.

“Following the foiling of the filing…” Took me longer to get my brain around this sentence than I would have liked.

Thanks for that!

Note to self: Finished.