© 2021 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://www.damninteresting.com/curio/a-taste-of-italy/

In the mid-1800s, Italy was consumed by two parallel fights: one to rid itself of Austrian domination (a holdover from the Holy Roman Empire) and the other for unification. At the time, Europe’s boot was a curious conglomeration of separate states, not all of which got along. Some were dominated by foreigners. One large section was ruled by the Pope, which Italians (who had been exposed to the secularist ideals of the French Revolution when Bonaparte invaded) were understandably none too keen on.

The Austrians, being as imperialistic as might be expected for an empire, reacted poorly to all this rabble-rousing and upheaval, and instituted a rule of firm Germanic discipline. Riots were put down, people were shot and occasionally tortured, and so on; the routine work of keeping an unruly oppressed population in its place.

As all of this was going on, curious graffiti began to spring up throughout Italy—graffiti that might not be entirely unexpected in the land that invented opera, but still unusual: large letters reading, ‘VIVA VERDI!’

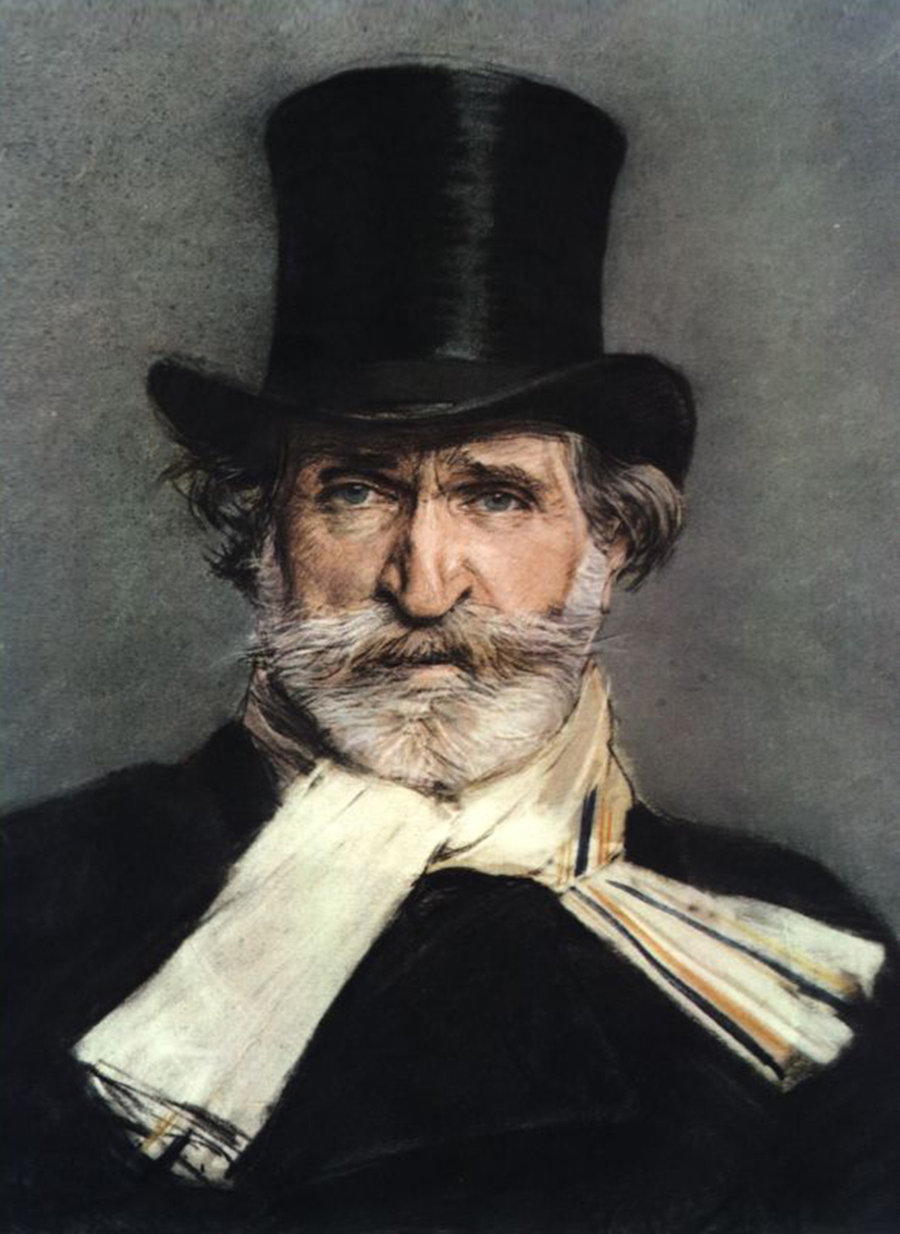

Giuseppe Verdi was the new big thing in opera, immensely popular, not least because of his rousing patriotic choruses that were taken to heart by the revolutionaries. But this specific graffiti became so common that Austrian officials wondered whether this outpouring of musical enthusiasm was in some way subversive; after all, Austrians didn’t go around scrawling ‘Heil Schubert’ on the walls.

The Austrians were right to wonder—because in fact this graffiti had little to do with music. ‘Verdi’ was an acronym for ‘Vittorio Emmanuele, Rè d’Italia’—Emmanuele being the king of Piedmont, and chief candidate for king of a united Italy. The graffiti was shorthand for ‘Long live Victor-Emmanuel, King of Italy’. Victor-Emmanuel eventually did become king, thanks mainly to the machinations of his prime minister, an opera-loving gentleman by the name of Cavour.

Incidentally, Cavour, who had long been manoeuvering for a war with Austria, was so delighted when one was declared that he startled passers-by as he rushed to his office window and belted out Verdi’s aria ‘Di quella pira’ from Il Trovatore. As the aria is one of the greatest test pieces for any tenor, one can only hope that Cavour had a fine voice.

The notoriously grumpy Verdi, who fully supported the aims of those who had used his name for propaganda, became a deputy for the new Italian parliament when it was formed, but simply voted as he was told before giving up in disgust and returning to his farm—where, to the end of his days, while producing gorgeous and dramatic music, he sullenly insisted on giving his occupation as ‘Farmer’ on every census.

© 2021 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://www.damninteresting.com/curio/a-taste-of-italy/

Since you enjoyed our work enough to print it out, and read it clear to the end, would you consider donating a few dollars at https://www.damninteresting.com/donate ?

Joe Green the farmer!

Point of personal privilege: Thanks for the new short form on my 68th birthday.